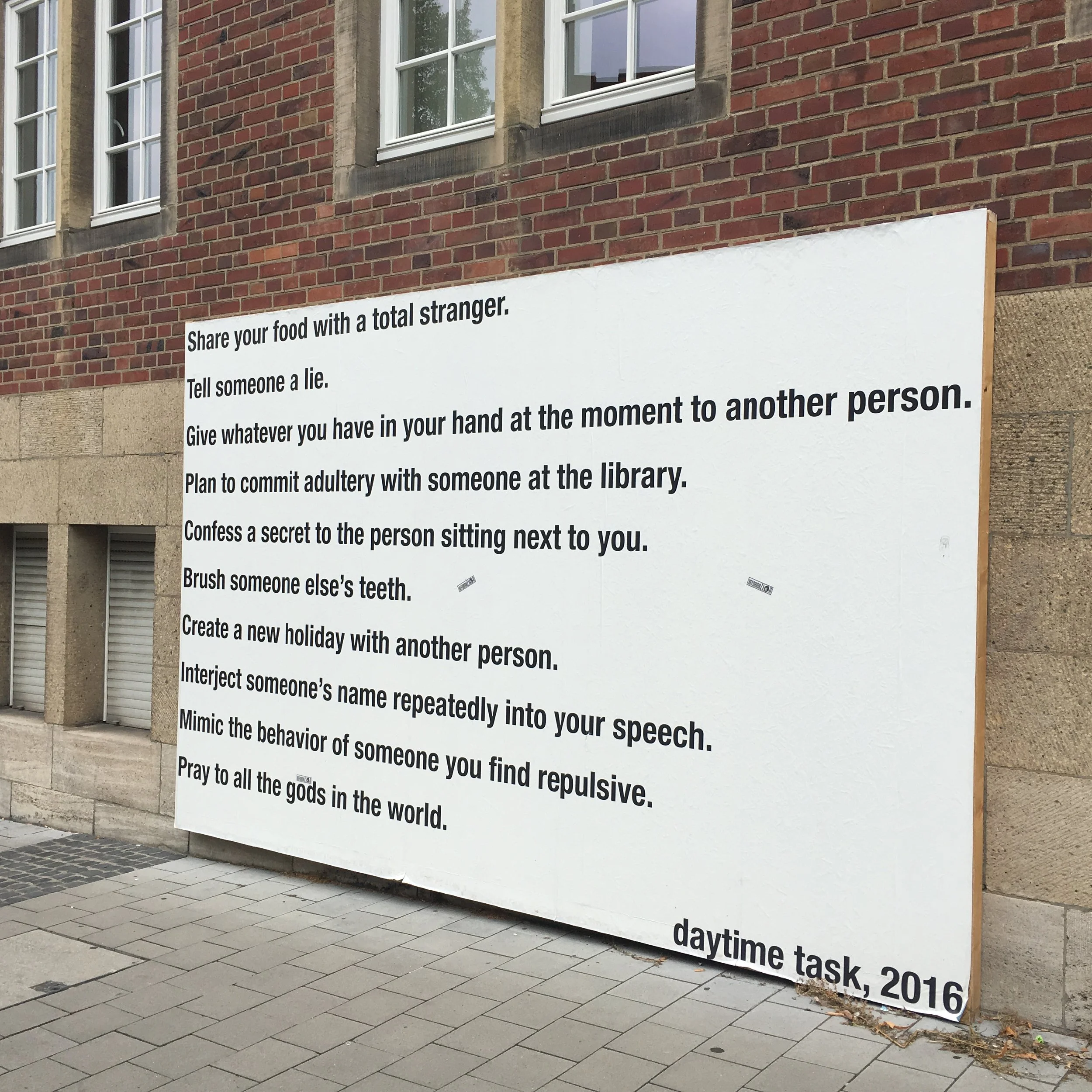

I think the Munster Skulptur Projekt might be my favourite international art event. A deeply thoughtful, once-a-decade, whole-of-city sculpture project that began in 1977, it refreshes a curiosity about public art and public space and a critical lens, whichever direction you look (“is that a park bench or is that a sculpture?”) as you treasure hunt your way all over the city on foot and by bike.

Seminal works from earlier iterations - Claes Oldenberg, Bruce Nauman, Dan Graham, Rosemarie Trockel, Ilya Kabakov - remain dotted across the city in this gradual accumulation of permanent incursions in the cityscape, with temporary works turning up in lakes, Asian grocers, community gardens and tattoo parlours.

I was lucky enough to come 10 years ago and so it’s a fascinating benchmark of your own life as well over a 10 year period - remembering who I was and how I felt at 27 and how it feels to be here, now 37. Wondering if I’ll get to come again when I’m 47.

I’ve spent the last few days riding all over the city and for better or worse, these are just some of the works that have lingered in my memory.

Mika Rottenberg, Cosmic Generator, 2017

Mika Rottenburg’s work perplexes me – in a knotty, compelling, deeply absorbing way. It resists a didactic translation – all you have to work with is slippery associations, surreal visuals and moments of strange humour – but if you give into it, a narrative does emerge and it is unsettling. There are things said about borders, about food and conspicuous consumption, labour, value and globalisation. The film element of Cosmic Generator is like a deep dive into the bowels of someone who garnished their tacos with some LSD. It explores an underworld – literally and intellectually – of mass production. People dressed as tacos and archetypal businessmen crawl through tunnels, towards or away from what we don’t know. Strange details punctuate throughout – the gaudy painting on the wall of the Chinese restaurant comes to life and the Ibis shits a golden egg while the deer vomits hi-vis yellow.

The camera pans through the shop-room after shop-room where bored Asian women are illuminated and/or buried in inflatables, fake flowers, lights and tinsel. It’s gloriously weird and the scenes are punctuated by close-ups of the smashing of coloured lightbulbs. To get to this 20-minute film, you have to enter through an otherwise-ordinary, though not abundantly stocked, Asian supermarket that carries elephant ceramics and blow-up pineapple tubes and tinsel and a faint sense of despair. It’s a useful framework and in moving through the store to the backroom that hosts the films you become an unwitting part of this whole transaction. And the bare shelves and unkempt store only heighten the gaudy excess of the film’s shop interiors. As a whole work/experience, it stays with you, even as you plough through countless other works in the course of the Project – wrestling to draw together all of your impressions and responses.

Aram Bartholl, 5V, 2017

I have to admit that my initial impression – based only on an image of the work – was that Aram Bartholl’s 5V was a strange affectation. So I’m glad I read about it before experiencing it. Despite the obvious technical expertise required to create the work – a campfire-generated phone charger – there is something staggeringly simple, elegant and poetic even, about Bartholl’s work. Connecting the world’s oldest innovation – fire – with its newest – the Internet and mobile communication, Bartholl challenges us to reimagine or remember communication as a space and encounter and as a consequence of community coming together around a fire; not as a series of tweets, texts or emojis. As a measure of how far we’ve departed from this old form of coming together and communicating, it was fascinating, and sad, to observe my own hesitation and quiet fear about approaching the work and having to talk even to the MSP invigilator. Though the smell of an open fire is so instantly familiar and comforting. I wasn’t expecting to like Bartholl’s work so I’m thrilled that it surprised me the way that it did because I really loved it.

Ayşe Erkmen, On Water, 2017

Ayşe Erkmen’s On Water is a treat, especially after several thankless kilometres biking through the industrial outskirts of Munster. A submerged pedestrian bridge that connects two sides of a large canal, visitors can cross the bridge and stroll from one side to the other and from a distance you appear as if walking on water, hence the title. Several things struck me while making my way across the back across.

The first, a sense of despondency that a risk-averse city like Sydney would never allow such a thing – no guard rails, no excess of life flotation devices, no lifeguards – and the second, a sense of possibility – to entertain the idea of what might happen if you did step off – that nanosecond where you did stand on water before plunging into the cold and rather unappealing canal – the risk and the folly and the faith. It was a brief, if intoxicating thought. The two sides of the canal are actually quite different – one very industrial, the other gentrified with a boardwalk and bars – so the incentive to cross and explore the other side is little to none, otherwise – and yet, historically, I imagine they worked in simpatico. My only criticism, if it could even be called that, was the deep and uncomfortable impression of the steel mesh bridge underfoot. Not even the cold refresh of water on red hot tired feet could distract from the pain. But perhaps with the temptation to step off and walk out onto the water being right there, a constant reminder of keeping your feet somewhere solid is no bad thing.

Pierre Huyghe, After Alive Ahead, 2017

Pierre Huyghe’s After Alive Ahead has been receiving countless plaudits but I can’t help but wonder if this is the art world illuminati overcompensating for the fact that Huyghe’s strange, abandoned environment in the old Munster ice-rink is beyond their grasp. Because it was certainly beyond mine.

Past encounters with Huyghe’s work have been highly memorable – his Frieze Projects aquarium in 2011, where a lobster took up residence in the skull of a Brancusi bronze sculpture; even his wonderfully bizarre environment at 2012 documenta – with its pink-legged dog and hive of bees-as-beard on a reclining marble statue, all in the wilderness surrounding Kassel’s lake. But After Alive Ahead felt disjointed and as empty as the part-excavated rink. Apparently there were peacocks who were meant to inhabit the space, but they became too traumatised and had to be removed. The connections between the absent birds, the crater-like surface of the rink, all muddy puddles and lumpen stalactites, and the illuminated fish tank at the centre were resolutely unclear and the introduction of an app, which projected hovering black pyramids on a camera screen was baffling. It seemed to promise a narrative – or at least a navigation of the space in some way – but I was left feeling like I was either not using it properly or using it properly and completely missing the point.

The whole experience, instead of feeling organically weird, felt stymied and staccatoed. Apparently an exploration of ecosystems, cell reproduction and cancer growth, After Alive Ahead ultimately felt overthought and a bit contrived. It made for a disappointing, unmemorable experience.

OTHER POSTS

-

2026

- Feb 2, 2026 NAVA Educator Guide: Introduction to Committing to Meaningful First Nations Projects in Education Settings Feb 2, 2026

- Jan 14, 2026 Art Guide Australia: The Beguiling Art of the Boyd Women Jan 14, 2026

- Jan 5, 2026 Routledge publication: Youth Programs in Art Museums - An International Perspective Jan 5, 2026

-

2025

- Dec 17, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Field Notes. A Grassroots Approach to Public Art Dec 17, 2025

- Dec 10, 2025 Olafur Eliasson: PRESENCE, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Dec 10, 2025

- Oct 15, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Material curiosities, MCA Primavera Oct 15, 2025

- Aug 28, 2025 Berlin trip: Connected Audiences Conference and some Art, Art, Art.... Aug 28, 2025

- Jul 2, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Studio profile of Monica Rani Rudhar Jul 2, 2025

- May 5, 2025 ABC Arts: Lauren Brincat, When do I breathe? May 5, 2025

- Apr 23, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Tina Havelock Stevens Apr 23, 2025

- Apr 5, 2025 Connected Audiences Conference - Culture & Young People: What could possibly go wrong? Apr 5, 2025

- Apr 4, 2025 ABC Arts: Thinking Together at Bundanon Apr 4, 2025

- Apr 2, 2025 Collecting: Living with Art book launch Apr 2, 2025

- Mar 7, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Mystery Road - Zanny Begg profile Mar 7, 2025

- Feb 4, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Home Truths - feature story Feb 4, 2025

-

2024

- Dec 21, 2024 ABC Arts: Yayoi Kusama at NGV International Dec 21, 2024

- Dec 2, 2024 Artlink magazine's 'Hyphen' issue published Dec 2, 2024

- Nov 25, 2024 Art writing workshop with Woollahra Art Gallery Nov 25, 2024

- Aug 3, 2024 Los Angeles art binge Aug 3, 2024

- Mar 11, 2024 Biennale of Sydney opening & publication Mar 11, 2024

- Mar 9, 2024 Melbourne work trip Mar 9, 2024

- Feb 10, 2024 NGA National Young Writers Digital Residency launches Feb 10, 2024

-

2023

- Dec 6, 2023 Teen Program Symposium: Walker Art Center Dec 6, 2023

- Jul 26, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: Hustle Harder Jul 26, 2023

- Jul 21, 2023 Publication day! Museum Teen Program How-To Kit Jul 21, 2023

- Jul 20, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: "A lesson in listening" Jul 20, 2023

- Jul 4, 2023 Art Party at The Condensery Jul 4, 2023

- Jun 13, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: "These artists shared their work via post, now the paint is almost dry on the result." Jun 13, 2023

- May 18, 2023 Panel talk: Australian Museums & Galleries Association National Conference May 18, 2023

-

2022

- Dec 1, 2022 Published outcomes - National Gallery of Australia: Digital Young Writers Mentorship Dec 1, 2022

- Nov 29, 2022 ABC Arts: 'Air' at QAGOMA Nov 29, 2022

- Aug 28, 2022 The Condensery - Somerset Regional Art Gallery: new youth engagement project - 'Things I Want To Say' Aug 28, 2022

- Aug 13, 2022 ABC Arts: Megan Cope is building a living, breathing artwork on Minjerribah Aug 13, 2022

- Jul 21, 2022 Exhibition essay: Topographies of painting - Gregory Hodge, Sullivan + Strumpf Jul 21, 2022

- Jul 2, 2022 ABC Arts: Richard Bell at documenta fifteen Jul 2, 2022

- Feb 28, 2022 National Gallery of Australia: Digital Young Writers Mentorship Feb 28, 2022

- Jan 5, 2022 Journal of Museum Education article: "Pockets of Resilience - the Digital Responses of Youth Collectives in Contemporary Art Museums During Lockdown." Jan 5, 2022

-

2021

- Nov 13, 2021 ABC Arts: Tarnanthi Nov 13, 2021

- Oct 27, 2021 A New Approach: Enduring Foundations, Bold Ambitions Oct 27, 2021

- Oct 16, 2021 Churchill Chat - Equity, Inclusion & the Impact of COVID-19 on the Arts Oct 16, 2021

- Aug 24, 2021 Art Collector: Pull Focus interview with Abdul Abdullah & Abdul-Rahman Abdullah Aug 24, 2021

- Aug 8, 2021 ABC Arts: Dean Cross and a spotlight on the work of Australia's regional galleries Aug 8, 2021

- Jun 30, 2021 ABC Arts: Hilma af Klint - The Secret Paintings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales Jun 30, 2021

-

2020

- Oct 24, 2020 Raise your voice: young people in the arts Oct 24, 2020

- Oct 1, 2020 Art Collector: Pull Focus interviews for Sydney Contemporary Oct 1, 2020

- Sep 4, 2020 Recommended reading - Teen Vogue Sep 4, 2020

- Jun 8, 2020 SAMAG Talk - Bringing it home: Innovation & Ideas from the Churchill Fellowship Jun 8, 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 MCA GENEXT Goes Online Jun 1, 2020

- May 23, 2020 Vale Frank Watters - Artlink magazine May 23, 2020

-

2019

- Nov 19, 2019 Churchill Fellowship Report - findings Nov 19, 2019

- Aug 21, 2019 Upcoming SAMAG Panel - Youth arts: why we should care what young people think Aug 21, 2019

- May 10, 2019 By young people for young people - A report on the impact of GENEXT at MCA Australia May 10, 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Art Collector Issue 87: 50 Things Collectors Should Know Feb 1, 2019

-

2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Artist texts: Clare Thackway Nov 23, 2018

- Oct 29, 2018 Announcement of Churchill Fellowship 2018 Oct 29, 2018

- Sep 30, 2018 Frida Kahlo at the Victoria & Albert Museum Sep 30, 2018

- Sep 7, 2018 Elizabeth Willing profile for Art Collector magazine Sep 7, 2018

- Aug 2, 2018 Beyond Community Engagement: Transforming Dialogues in Art, Education and the Cultural Sphere Aug 2, 2018

- Jun 21, 2018 Spotlight on MCA Young Guides Jun 21, 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Art Collector Issue 84: Undiscovered Feb 1, 2018

-

2017

- Aug 30, 2017 Skulptur Projecke Münster 2017 Aug 30, 2017

- Jul 26, 2017 Te Tuhi Talks Jul 26, 2017

- Apr 2, 2017 New role: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia Apr 2, 2017

- Jan 19, 2017 Louise Paramor profile for Art Collector magazine, issue 78 Jan 19, 2017

-

2016

- Dec 1, 2016 Craft Council UK – Make:Shift conference, Manchester, 10-11 Nov, 2016 Dec 1, 2016

- Oct 30, 2016 Alison Croggon on the arts funding crisis and the importance of criticism Oct 30, 2016

- Apr 27, 2016 Lottie Consalvo: mid-fall, Alaska Projects Apr 27, 2016

- Mar 18, 2016 20th Biennale of Sydney: The future is here it's just not evenly distributed Mar 18, 2016

-

2015

- Nov 22, 2015 Celeste Boursier-Mougenot at the NGV Nov 22, 2015

- Sep 22, 2015 Educating People Like Us Sep 22, 2015

- Aug 2, 2015 What It Means to be Me, Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo, 26 July 2015 Aug 2, 2015

- Jul 12, 2015 More Marina Magic Jul 12, 2015

- Jul 12, 2015 Art Collector cover story Jul 12, 2015

- Jun 25, 2015 Lessons learnt: Kaldor regional progress report Jun 25, 2015

- May 5, 2015 Kaldor pilots regional engagement project May 5, 2015

-

2014

- Aug 21, 2014 Melbourne Art Fair 2014 Aug 21, 2014

- Jun 24, 2014 Fresh Faces Symposium: Art Gallery of New South Wales Jun 24, 2014

- May 24, 2014 REVIEW: Sleepers Awake, MCA C3West Project, Bungaribee May 24, 2014

- Feb 20, 2014 Kevin Chin profile for Art Collector magazine Feb 20, 2014

- Feb 9, 2014 Artlink review: 21st Century Portraits Feb 9, 2014

- Jan 12, 2014 REVIEW: Christian Boltanski, Chance, Carriageworks Jan 12, 2014

-

2013

- Sep 20, 2013 The problem with 'Australia' Sep 20, 2013

- Sep 4, 2013 Margate: An away day and a visit to Turner Contemporary Sep 4, 2013

- Jul 28, 2013 A round-up: Miles Aldridge, Somerset House; Katharina Fritsch, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square; Michael Landy, ‘Saints Alive’, National Gallery Jul 28, 2013

- Jul 21, 2013 Peckham weekends Jul 21, 2013

- Jul 11, 2013 Harpa Concert Hall, Reykjavik Jul 11, 2013

- Jun 4, 2013 St Paul-de-Vence Jun 4, 2013

- May 30, 2013 A visit to Paul Cezanne's studio May 30, 2013

-

2012

- Oct 30, 2012 REVIEW: DOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Germany Oct 30, 2012

- Oct 28, 2012 Tino Sehgal, These Associations, Tate Modern, London Oct 28, 2012

- Aug 4, 2012 Jeremy Deller, Sacrilege, Burgess Park, London Aug 4, 2012

- Apr 14, 2012 REVIEW: Martin Creed, Sketch Nightclub, London Apr 14, 2012

-

2010

- Jul 19, 2010 Christian Boltanski, Les archives du coeur, Serpentine Gallery, London Jul 19, 2010

- Jul 9, 2010 REVIEW: 1:1 Architects Build Small Spaces, Victoria & Albert Museum, London Jul 9, 2010

- Jul 5, 2010 REVIEW: EXPOSED: Voyeurism, Surveillance & the Camera, Tate Modern, London Jul 5, 2010

- Jun 21, 2010 REVIEW: Sean Scully New Work, Timothy Taylor Gallery, London Jun 21, 2010

- Jun 14, 2010 Yinka Shonibare MBE, “Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle”, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square Jun 14, 2010

- May 20, 2010 REVIEW: Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, Barbican Centre, London May 20, 2010

- May 16, 2010 REVIEW: Decode: Digital Design Sensation, Victoria & Albert Museum, London May 16, 2010

- May 9, 2010 REVIEW: Olafur Eliasson: Take Your Time, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney May 9, 2010

-

2009

- Dec 1, 2009 REVIEW: Anish Kapoor, Royal Academy of Arts Dec 1, 2009

- Mar 27, 2009 REVIEW: Mythologies, Haunch of Venison Mar 27, 2009

-

2008

- Sep 17, 2008 REVIEW: Suzanne Treister, ALCHEMY, Annely Juda Fine Art Sep 17, 2008