10 July – 8 August 2010

I’ve been long been drawn to the work of French conceptual and installation artist Christian Boltanski. I don’t really remember my first encounter with his practice – it may have been an overwrought art theory lecture on trauma? – but his decades-long practice, which might best be described visually as a sort of mournful poetry in its exploration of memory, absence, loss and suffering, continues to resonate.

While much of Boltanski’s work is rooted in an awareness of the Holocaust and its social and historical consequences, universally his work is about reclaiming the individual experience within History and Memory and the ultimately ephemeral nature of both life and ‘little M’ memory.

The opportunity to contribute to Boltanski’s latest work thus proved irresistible.

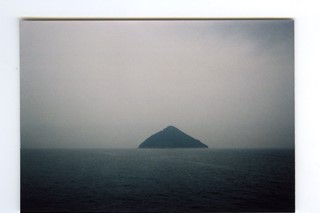

In Les archives du coeur, or The Heart Archive, Boltanski returns to the fundamental idea of his 2005 work Le Coeur, where a single light bulb flickered on and off to the rhythm of the artist’s recorded heartbeat, a neat visual expression for the connection between darkness and revelation and life and death. In Les archives, Boltanski re-visits this idea of the heartbeat – as both a function of the artwork and as a metaphorical and physiological testimony to the singularity of each life lived. Began in 2005, Les archives, as an encounter, is an unassuming white office space with the equipment to simply record the heartbeat of each visitor. These heartbeats – named and dated – are then added to an ongoing archive now in excess of one million recordings collected from all over the world. As an experience, Les archives is oddly mechanical and while each visitor takes a CD of their recorded heartbeat away with them, it is not heard during the recording process, which is done with a small electronic stethoscope pressed simply to the chest and plugged in to a computer. The magnitude – and the poetry – of the gesture lies in the vision of this simple 30 second soundtrack to the very essence of your being, being held with so many others in a specially designated archive on the uninhabited island of Ejima in the Sea of Japan. A 30 second soundtrack that says I was here and my existence was real. For such a perfunctory encounter it is a profoundly overwhelming concept.

In January this year the archive was broadcast throughout Boltanski’s epic installation Personnes at the Grand Palais in Paris for Monumenta 2010. Not having experienced the work in this context, with the heartbeats echoing throughout the 13,500 square metre space as visitors navigated their way through the carefully arranged piles of abandoned clothes, the imaginative and emotional possibilities are but endless. If Boltanski’s other works are any measure of things, the resounding effect in this environment was undoubtedly an awareness of the human experience as both tangible and fleeting.

Boltanski has said that he is interested in “what I call ‘little memory’, an emotional memory, an everyday knowledge, the contrary of the Memory with a capital M that is preserved in history books. This little memory, which for me is what makes us unique, is extremely fragile and it disappears with death. This loss of identity, this equalisation in forgetting, is very difficult to accept.” Les archives du coeur is both a material and a philosophical counter to this forgetting, and while it is hugely confronting to realise that in recording life you are ultimately acknowledging death, participating in Boltanski’s work is affirming above and beyond anything else – of the preciousness of life and of the value of each of us as individuals.

This is the first time Les archives du coeur has been shown in the United Kingdom and it is should not be missed.

OTHER POSTS

-

2026

- Feb 2, 2026 NAVA Educator Guide: Introduction to Committing to Meaningful First Nations Projects in Education Settings Feb 2, 2026

- Jan 14, 2026 Art Guide Australia: The Beguiling Art of the Boyd Women Jan 14, 2026

- Jan 5, 2026 Routledge publication: Youth Programs in Art Museums - An International Perspective Jan 5, 2026

-

2025

- Dec 17, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Field Notes. A Grassroots Approach to Public Art Dec 17, 2025

- Dec 10, 2025 Olafur Eliasson: PRESENCE, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Dec 10, 2025

- Oct 15, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Material curiosities, MCA Primavera Oct 15, 2025

- Aug 28, 2025 Berlin trip: Connected Audiences Conference and some Art, Art, Art.... Aug 28, 2025

- Jul 2, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Studio profile of Monica Rani Rudhar Jul 2, 2025

- May 5, 2025 ABC Arts: Lauren Brincat, When do I breathe? May 5, 2025

- Apr 23, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Tina Havelock Stevens Apr 23, 2025

- Apr 5, 2025 Connected Audiences Conference - Culture & Young People: What could possibly go wrong? Apr 5, 2025

- Apr 4, 2025 ABC Arts: Thinking Together at Bundanon Apr 4, 2025

- Apr 2, 2025 Collecting: Living with Art book launch Apr 2, 2025

- Mar 7, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Mystery Road - Zanny Begg profile Mar 7, 2025

- Feb 4, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Home Truths - feature story Feb 4, 2025

-

2024

- Dec 21, 2024 ABC Arts: Yayoi Kusama at NGV International Dec 21, 2024

- Dec 2, 2024 Artlink magazine's 'Hyphen' issue published Dec 2, 2024

- Nov 25, 2024 Art writing workshop with Woollahra Art Gallery Nov 25, 2024

- Aug 3, 2024 Los Angeles art binge Aug 3, 2024

- Mar 11, 2024 Biennale of Sydney opening & publication Mar 11, 2024

- Mar 9, 2024 Melbourne work trip Mar 9, 2024

- Feb 10, 2024 NGA National Young Writers Digital Residency launches Feb 10, 2024

-

2023

- Dec 6, 2023 Teen Program Symposium: Walker Art Center Dec 6, 2023

- Jul 26, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: Hustle Harder Jul 26, 2023

- Jul 21, 2023 Publication day! Museum Teen Program How-To Kit Jul 21, 2023

- Jul 20, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: "A lesson in listening" Jul 20, 2023

- Jul 4, 2023 Art Party at The Condensery Jul 4, 2023

- Jun 13, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: "These artists shared their work via post, now the paint is almost dry on the result." Jun 13, 2023

- May 18, 2023 Panel talk: Australian Museums & Galleries Association National Conference May 18, 2023

-

2022

- Dec 1, 2022 Published outcomes - National Gallery of Australia: Digital Young Writers Mentorship Dec 1, 2022

- Nov 29, 2022 ABC Arts: 'Air' at QAGOMA Nov 29, 2022

- Aug 28, 2022 The Condensery - Somerset Regional Art Gallery: new youth engagement project - 'Things I Want To Say' Aug 28, 2022

- Aug 13, 2022 ABC Arts: Megan Cope is building a living, breathing artwork on Minjerribah Aug 13, 2022

- Jul 21, 2022 Exhibition essay: Topographies of painting - Gregory Hodge, Sullivan + Strumpf Jul 21, 2022

- Jul 2, 2022 ABC Arts: Richard Bell at documenta fifteen Jul 2, 2022

- Feb 28, 2022 National Gallery of Australia: Digital Young Writers Mentorship Feb 28, 2022

- Jan 5, 2022 Journal of Museum Education article: "Pockets of Resilience - the Digital Responses of Youth Collectives in Contemporary Art Museums During Lockdown." Jan 5, 2022

-

2021

- Nov 13, 2021 ABC Arts: Tarnanthi Nov 13, 2021

- Oct 27, 2021 A New Approach: Enduring Foundations, Bold Ambitions Oct 27, 2021

- Oct 16, 2021 Churchill Chat - Equity, Inclusion & the Impact of COVID-19 on the Arts Oct 16, 2021

- Aug 24, 2021 Art Collector: Pull Focus interview with Abdul Abdullah & Abdul-Rahman Abdullah Aug 24, 2021

- Aug 8, 2021 ABC Arts: Dean Cross and a spotlight on the work of Australia's regional galleries Aug 8, 2021

- Jun 30, 2021 ABC Arts: Hilma af Klint - The Secret Paintings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales Jun 30, 2021

-

2020

- Oct 24, 2020 Raise your voice: young people in the arts Oct 24, 2020

- Oct 1, 2020 Art Collector: Pull Focus interviews for Sydney Contemporary Oct 1, 2020

- Sep 4, 2020 Recommended reading - Teen Vogue Sep 4, 2020

- Jun 8, 2020 SAMAG Talk - Bringing it home: Innovation & Ideas from the Churchill Fellowship Jun 8, 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 MCA GENEXT Goes Online Jun 1, 2020

- May 23, 2020 Vale Frank Watters - Artlink magazine May 23, 2020

-

2019

- Nov 19, 2019 Churchill Fellowship Report - findings Nov 19, 2019

- Aug 21, 2019 Upcoming SAMAG Panel - Youth arts: why we should care what young people think Aug 21, 2019

- May 10, 2019 By young people for young people - A report on the impact of GENEXT at MCA Australia May 10, 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Art Collector Issue 87: 50 Things Collectors Should Know Feb 1, 2019

-

2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Artist texts: Clare Thackway Nov 23, 2018

- Oct 29, 2018 Announcement of Churchill Fellowship 2018 Oct 29, 2018

- Sep 30, 2018 Frida Kahlo at the Victoria & Albert Museum Sep 30, 2018

- Sep 7, 2018 Elizabeth Willing profile for Art Collector magazine Sep 7, 2018

- Aug 2, 2018 Beyond Community Engagement: Transforming Dialogues in Art, Education and the Cultural Sphere Aug 2, 2018

- Jun 21, 2018 Spotlight on MCA Young Guides Jun 21, 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Art Collector Issue 84: Undiscovered Feb 1, 2018

-

2017

- Aug 30, 2017 Skulptur Projecke Münster 2017 Aug 30, 2017

- Jul 26, 2017 Te Tuhi Talks Jul 26, 2017

- Apr 2, 2017 New role: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia Apr 2, 2017

- Jan 19, 2017 Louise Paramor profile for Art Collector magazine, issue 78 Jan 19, 2017

-

2016

- Dec 1, 2016 Craft Council UK – Make:Shift conference, Manchester, 10-11 Nov, 2016 Dec 1, 2016

- Oct 30, 2016 Alison Croggon on the arts funding crisis and the importance of criticism Oct 30, 2016

- Apr 27, 2016 Lottie Consalvo: mid-fall, Alaska Projects Apr 27, 2016

- Mar 18, 2016 20th Biennale of Sydney: The future is here it's just not evenly distributed Mar 18, 2016

-

2015

- Nov 22, 2015 Celeste Boursier-Mougenot at the NGV Nov 22, 2015

- Sep 22, 2015 Educating People Like Us Sep 22, 2015

- Aug 2, 2015 What It Means to be Me, Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo, 26 July 2015 Aug 2, 2015

- Jul 12, 2015 More Marina Magic Jul 12, 2015

- Jul 12, 2015 Art Collector cover story Jul 12, 2015

- Jun 25, 2015 Lessons learnt: Kaldor regional progress report Jun 25, 2015

- May 5, 2015 Kaldor pilots regional engagement project May 5, 2015

-

2014

- Aug 21, 2014 Melbourne Art Fair 2014 Aug 21, 2014

- Jun 24, 2014 Fresh Faces Symposium: Art Gallery of New South Wales Jun 24, 2014

- May 24, 2014 REVIEW: Sleepers Awake, MCA C3West Project, Bungaribee May 24, 2014

- Feb 20, 2014 Kevin Chin profile for Art Collector magazine Feb 20, 2014

- Feb 9, 2014 Artlink review: 21st Century Portraits Feb 9, 2014

- Jan 12, 2014 REVIEW: Christian Boltanski, Chance, Carriageworks Jan 12, 2014

-

2013

- Sep 20, 2013 The problem with 'Australia' Sep 20, 2013

- Sep 4, 2013 Margate: An away day and a visit to Turner Contemporary Sep 4, 2013

- Jul 28, 2013 A round-up: Miles Aldridge, Somerset House; Katharina Fritsch, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square; Michael Landy, ‘Saints Alive’, National Gallery Jul 28, 2013

- Jul 21, 2013 Peckham weekends Jul 21, 2013

- Jul 11, 2013 Harpa Concert Hall, Reykjavik Jul 11, 2013

- Jun 4, 2013 St Paul-de-Vence Jun 4, 2013

- May 30, 2013 A visit to Paul Cezanne's studio May 30, 2013

-

2012

- Oct 30, 2012 REVIEW: DOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Germany Oct 30, 2012

- Oct 28, 2012 Tino Sehgal, These Associations, Tate Modern, London Oct 28, 2012

- Aug 4, 2012 Jeremy Deller, Sacrilege, Burgess Park, London Aug 4, 2012

- Apr 14, 2012 REVIEW: Martin Creed, Sketch Nightclub, London Apr 14, 2012

-

2010

- Jul 19, 2010 Christian Boltanski, Les archives du coeur, Serpentine Gallery, London Jul 19, 2010

- Jul 9, 2010 REVIEW: 1:1 Architects Build Small Spaces, Victoria & Albert Museum, London Jul 9, 2010

- Jul 5, 2010 REVIEW: EXPOSED: Voyeurism, Surveillance & the Camera, Tate Modern, London Jul 5, 2010

- Jun 21, 2010 REVIEW: Sean Scully New Work, Timothy Taylor Gallery, London Jun 21, 2010

- Jun 14, 2010 Yinka Shonibare MBE, “Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle”, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square Jun 14, 2010

- May 20, 2010 REVIEW: Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, Barbican Centre, London May 20, 2010

- May 16, 2010 REVIEW: Decode: Digital Design Sensation, Victoria & Albert Museum, London May 16, 2010

- May 9, 2010 REVIEW: Olafur Eliasson: Take Your Time, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney May 9, 2010

-

2009

- Dec 1, 2009 REVIEW: Anish Kapoor, Royal Academy of Arts Dec 1, 2009

- Mar 27, 2009 REVIEW: Mythologies, Haunch of Venison Mar 27, 2009

-

2008

- Sep 17, 2008 REVIEW: Suzanne Treister, ALCHEMY, Annely Juda Fine Art Sep 17, 2008