The latest issue of the always wonderful Artlink (vol.34 no.1) features a brilliant review of 21st Century Portraits by Margot Osborne.

And by brilliant I mean fair, considered, intelligent and personally gratifying.

Read it here.

OTHER POSTS

-

2026

- Feb 2, 2026 NAVA Educator Guide: Introduction to Committing to Meaningful First Nations Projects in Education Settings Feb 2, 2026

- Jan 14, 2026 Art Guide Australia: The Beguiling Art of the Boyd Women Jan 14, 2026

- Jan 5, 2026 Routledge publication: Youth Programs in Art Museums - An International Perspective Jan 5, 2026

-

2025

- Dec 17, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Field Notes. A Grassroots Approach to Public Art Dec 17, 2025

- Dec 10, 2025 Olafur Eliasson: PRESENCE, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Dec 10, 2025

- Oct 15, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Material curiosities, MCA Primavera Oct 15, 2025

- Aug 28, 2025 Berlin trip: Connected Audiences Conference and some Art, Art, Art.... Aug 28, 2025

- Jul 2, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Studio profile of Monica Rani Rudhar Jul 2, 2025

- May 5, 2025 ABC Arts: Lauren Brincat, When do I breathe? May 5, 2025

- Apr 23, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Tina Havelock Stevens Apr 23, 2025

- Apr 5, 2025 Connected Audiences Conference - Culture & Young People: What could possibly go wrong? Apr 5, 2025

- Apr 4, 2025 ABC Arts: Thinking Together at Bundanon Apr 4, 2025

- Apr 2, 2025 Collecting: Living with Art book launch Apr 2, 2025

- Mar 7, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Mystery Road - Zanny Begg profile Mar 7, 2025

- Feb 4, 2025 Art Guide Australia: Home Truths - feature story Feb 4, 2025

-

2024

- Dec 21, 2024 ABC Arts: Yayoi Kusama at NGV International Dec 21, 2024

- Dec 2, 2024 Artlink magazine's 'Hyphen' issue published Dec 2, 2024

- Nov 25, 2024 Art writing workshop with Woollahra Art Gallery Nov 25, 2024

- Aug 3, 2024 Los Angeles art binge Aug 3, 2024

- Mar 11, 2024 Biennale of Sydney opening & publication Mar 11, 2024

- Mar 9, 2024 Melbourne work trip Mar 9, 2024

- Feb 10, 2024 NGA National Young Writers Digital Residency launches Feb 10, 2024

-

2023

- Dec 6, 2023 Teen Program Symposium: Walker Art Center Dec 6, 2023

- Jul 26, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: Hustle Harder Jul 26, 2023

- Jul 21, 2023 Publication day! Museum Teen Program How-To Kit Jul 21, 2023

- Jul 20, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: "A lesson in listening" Jul 20, 2023

- Jul 4, 2023 Art Party at The Condensery Jul 4, 2023

- Jun 13, 2023 Sydney Morning Herald: "These artists shared their work via post, now the paint is almost dry on the result." Jun 13, 2023

- May 18, 2023 Panel talk: Australian Museums & Galleries Association National Conference May 18, 2023

-

2022

- Dec 1, 2022 Published outcomes - National Gallery of Australia: Digital Young Writers Mentorship Dec 1, 2022

- Nov 29, 2022 ABC Arts: 'Air' at QAGOMA Nov 29, 2022

- Aug 28, 2022 The Condensery - Somerset Regional Art Gallery: new youth engagement project - 'Things I Want To Say' Aug 28, 2022

- Aug 13, 2022 ABC Arts: Megan Cope is building a living, breathing artwork on Minjerribah Aug 13, 2022

- Jul 21, 2022 Exhibition essay: Topographies of painting - Gregory Hodge, Sullivan + Strumpf Jul 21, 2022

- Jul 2, 2022 ABC Arts: Richard Bell at documenta fifteen Jul 2, 2022

- Feb 28, 2022 National Gallery of Australia: Digital Young Writers Mentorship Feb 28, 2022

- Jan 5, 2022 Journal of Museum Education article: "Pockets of Resilience - the Digital Responses of Youth Collectives in Contemporary Art Museums During Lockdown." Jan 5, 2022

-

2021

- Nov 13, 2021 ABC Arts: Tarnanthi Nov 13, 2021

- Oct 27, 2021 A New Approach: Enduring Foundations, Bold Ambitions Oct 27, 2021

- Oct 16, 2021 Churchill Chat - Equity, Inclusion & the Impact of COVID-19 on the Arts Oct 16, 2021

- Aug 24, 2021 Art Collector: Pull Focus interview with Abdul Abdullah & Abdul-Rahman Abdullah Aug 24, 2021

- Aug 8, 2021 ABC Arts: Dean Cross and a spotlight on the work of Australia's regional galleries Aug 8, 2021

- Jun 30, 2021 ABC Arts: Hilma af Klint - The Secret Paintings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales Jun 30, 2021

-

2020

- Oct 24, 2020 Raise your voice: young people in the arts Oct 24, 2020

- Oct 1, 2020 Art Collector: Pull Focus interviews for Sydney Contemporary Oct 1, 2020

- Sep 4, 2020 Recommended reading - Teen Vogue Sep 4, 2020

- Jun 8, 2020 SAMAG Talk - Bringing it home: Innovation & Ideas from the Churchill Fellowship Jun 8, 2020

- Jun 1, 2020 MCA GENEXT Goes Online Jun 1, 2020

- May 23, 2020 Vale Frank Watters - Artlink magazine May 23, 2020

-

2019

- Nov 19, 2019 Churchill Fellowship Report - findings Nov 19, 2019

- Aug 21, 2019 Upcoming SAMAG Panel - Youth arts: why we should care what young people think Aug 21, 2019

- May 10, 2019 By young people for young people - A report on the impact of GENEXT at MCA Australia May 10, 2019

- Feb 1, 2019 Art Collector Issue 87: 50 Things Collectors Should Know Feb 1, 2019

-

2018

- Nov 23, 2018 Artist texts: Clare Thackway Nov 23, 2018

- Oct 29, 2018 Announcement of Churchill Fellowship 2018 Oct 29, 2018

- Sep 30, 2018 Frida Kahlo at the Victoria & Albert Museum Sep 30, 2018

- Sep 7, 2018 Elizabeth Willing profile for Art Collector magazine Sep 7, 2018

- Aug 2, 2018 Beyond Community Engagement: Transforming Dialogues in Art, Education and the Cultural Sphere Aug 2, 2018

- Jun 21, 2018 Spotlight on MCA Young Guides Jun 21, 2018

- Feb 1, 2018 Art Collector Issue 84: Undiscovered Feb 1, 2018

-

2017

- Aug 30, 2017 Skulptur Projecke Münster 2017 Aug 30, 2017

- Jul 26, 2017 Te Tuhi Talks Jul 26, 2017

- Apr 2, 2017 New role: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia Apr 2, 2017

- Jan 19, 2017 Louise Paramor profile for Art Collector magazine, issue 78 Jan 19, 2017

-

2016

- Dec 1, 2016 Craft Council UK – Make:Shift conference, Manchester, 10-11 Nov, 2016 Dec 1, 2016

- Oct 30, 2016 Alison Croggon on the arts funding crisis and the importance of criticism Oct 30, 2016

- Apr 27, 2016 Lottie Consalvo: mid-fall, Alaska Projects Apr 27, 2016

- Mar 18, 2016 20th Biennale of Sydney: The future is here it's just not evenly distributed Mar 18, 2016

-

2015

- Nov 22, 2015 Celeste Boursier-Mougenot at the NGV Nov 22, 2015

- Sep 22, 2015 Educating People Like Us Sep 22, 2015

- Aug 2, 2015 What It Means to be Me, Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo, 26 July 2015 Aug 2, 2015

- Jul 12, 2015 More Marina Magic Jul 12, 2015

- Jul 12, 2015 Art Collector cover story Jul 12, 2015

- Jun 25, 2015 Lessons learnt: Kaldor regional progress report Jun 25, 2015

- May 5, 2015 Kaldor pilots regional engagement project May 5, 2015

-

2014

- Aug 21, 2014 Melbourne Art Fair 2014 Aug 21, 2014

- Jun 24, 2014 Fresh Faces Symposium: Art Gallery of New South Wales Jun 24, 2014

- May 24, 2014 REVIEW: Sleepers Awake, MCA C3West Project, Bungaribee May 24, 2014

- Feb 20, 2014 Kevin Chin profile for Art Collector magazine Feb 20, 2014

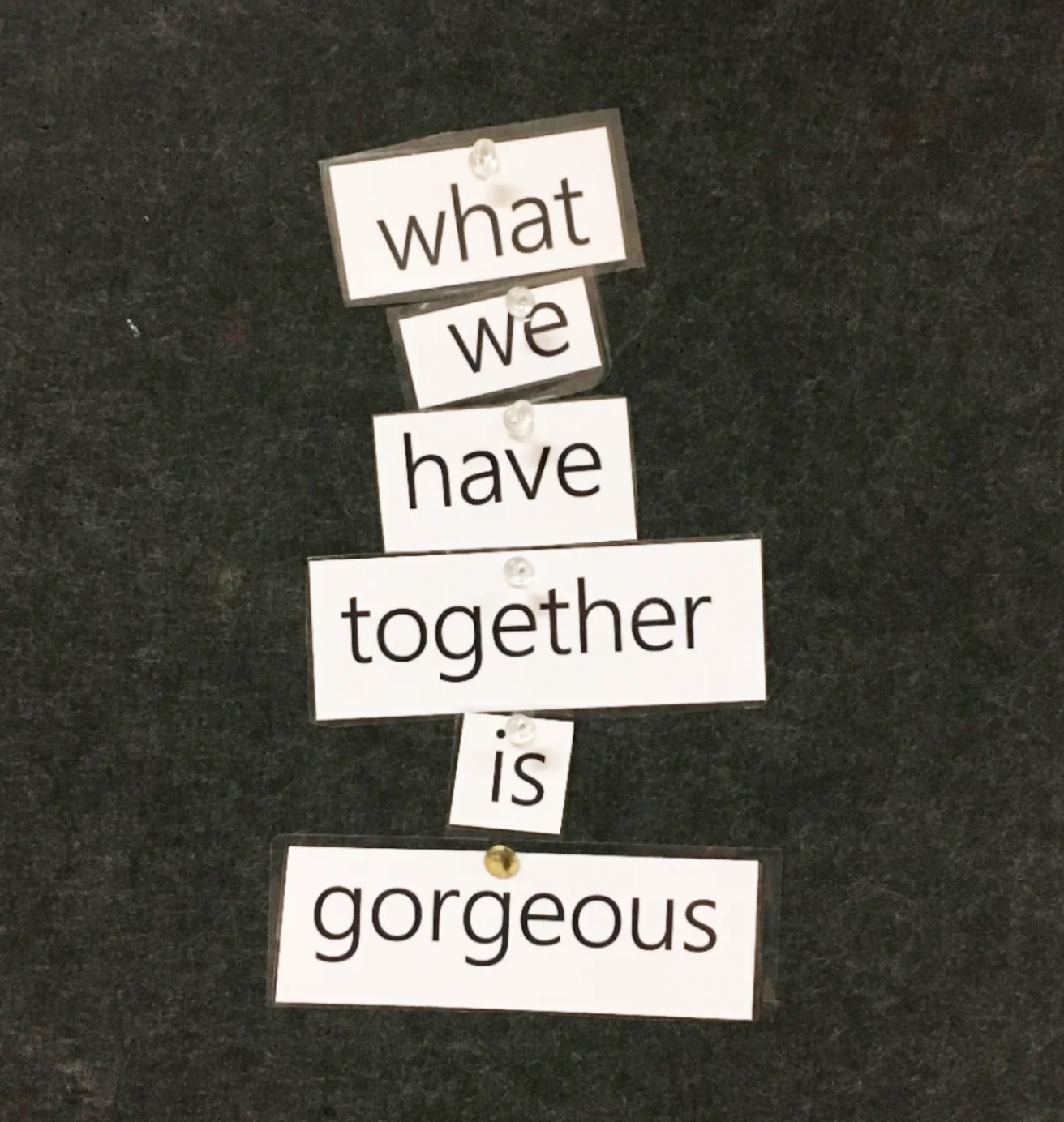

- Feb 9, 2014 Artlink review: 21st Century Portraits Feb 9, 2014

- Jan 12, 2014 REVIEW: Christian Boltanski, Chance, Carriageworks Jan 12, 2014

-

2013

- Sep 20, 2013 The problem with 'Australia' Sep 20, 2013

- Sep 4, 2013 Margate: An away day and a visit to Turner Contemporary Sep 4, 2013

- Jul 28, 2013 A round-up: Miles Aldridge, Somerset House; Katharina Fritsch, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square; Michael Landy, ‘Saints Alive’, National Gallery Jul 28, 2013

- Jul 21, 2013 Peckham weekends Jul 21, 2013

- Jul 11, 2013 Harpa Concert Hall, Reykjavik Jul 11, 2013

- Jun 4, 2013 St Paul-de-Vence Jun 4, 2013

- May 30, 2013 A visit to Paul Cezanne's studio May 30, 2013

-

2012

- Oct 30, 2012 REVIEW: DOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Germany Oct 30, 2012

- Oct 28, 2012 Tino Sehgal, These Associations, Tate Modern, London Oct 28, 2012

- Aug 4, 2012 Jeremy Deller, Sacrilege, Burgess Park, London Aug 4, 2012

- Apr 14, 2012 REVIEW: Martin Creed, Sketch Nightclub, London Apr 14, 2012

-

2010

- Jul 19, 2010 Christian Boltanski, Les archives du coeur, Serpentine Gallery, London Jul 19, 2010

- Jul 9, 2010 REVIEW: 1:1 Architects Build Small Spaces, Victoria & Albert Museum, London Jul 9, 2010

- Jul 5, 2010 REVIEW: EXPOSED: Voyeurism, Surveillance & the Camera, Tate Modern, London Jul 5, 2010

- Jun 21, 2010 REVIEW: Sean Scully New Work, Timothy Taylor Gallery, London Jun 21, 2010

- Jun 14, 2010 Yinka Shonibare MBE, “Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle”, Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square Jun 14, 2010

- May 20, 2010 REVIEW: Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, Barbican Centre, London May 20, 2010

- May 16, 2010 REVIEW: Decode: Digital Design Sensation, Victoria & Albert Museum, London May 16, 2010

- May 9, 2010 REVIEW: Olafur Eliasson: Take Your Time, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney May 9, 2010

-

2009

- Dec 1, 2009 REVIEW: Anish Kapoor, Royal Academy of Arts Dec 1, 2009

- Mar 27, 2009 REVIEW: Mythologies, Haunch of Venison Mar 27, 2009

-

2008

- Sep 17, 2008 REVIEW: Suzanne Treister, ALCHEMY, Annely Juda Fine Art Sep 17, 2008